Sound as the Core Concept

An engineer steps out of darkness and activates a 100-year-old engine on which the Kubota emblem is engraved.

"This Sound. The beginning of everything."

The engine reaches a steady rhythm and starts to generate power. That power creates sound — a rhythm. In sync with this sound, the video transitions to images of a present-day Kubota Engine factory. The engine sounds and factory sounds grow more numerous, ultimately becoming music. A melody is played, and the whole screen fills with harmony.

This concept film was designed around the core concept of sound, rather than using words or written messages.

When it came to conveying Kubota Engine's 100 years of history and progress to people around the world, we thought that rather than using words that would have to be translated into lots of different languages, we would let viewers experience the actual sounds of our factories, allowing them to develop their own sense of our history and present through the power of their imagination.

(The king of comedy, Charlie Chaplin produced a large number of silent movie masterpieces, and even in the era of the talking picture, his films still elicit laughter, tears and countless other emotions using only visual expression and pantomime, rather than words. When asked why he didn't include speech in his films, Chaplin allegedly replied that his films wouldn't be able to reach people around the world if they just used English.)

By designing this video around the concept of sound, Kubota Engine has achieved that same goal.

The music played in this video is wholly comprised of sounds made by Kubota engines, and in-situ sounds recorded at Kubota factories.

"This Sound. The beginning of everything."

Just as these words suggest, everything started with this sound. The music, made by combining actual sounds from factory floors, accompanies a video of Kubota engines being assembled and shipped to customers worldwide, and builds to a grand finale.

This video can also be seen as a sort of orchestral performance.

The engineer who appears at the beginning is the conductor. The factory sounds are the instruments, and the engineers working on engine production are the performers. The Kubota factory is the concert hall, and on the program is the ballet piece Boléro by Maurice Ravel.

The solo performance of a 100-year-old Kubota engine ultimately transforms into a musical soundscape of many performers, much like an orchestra, perhaps expressing something of Kubota Engine's manufacturing processes, which are unique the world over.

Meticulous Design and Creative Passion

The music performed by Kubota's engines and factories is the ballet piece Boléro by Maurice Ravel.

But why choose Boléro? There were a few reasons for this.

Ravel was born in 1875. Kubota's founder Gonshiro Kubota was born in 1870, so both men were part of the same generation. Moreover, Boléro was first performed in 1928. The first Kubota engine was built in 1922, very close in time to the birth of this piece of music.

With all this in mind, let's consider some more reasons why Boléro was chosen.

Although Maurice Ravel was French, his father was a Swiss inventor and his mother was from the Basque Country of Spain. Ravel's music is said to combine the precision and skill of a Swiss clockmaker with a distinctively Spanish passion and breadth of color, and it may be for this reason that he has garnered such a great reputation, even being called a "magician" of the orchestra.

Kubota engines, on the other hand, push the limits of casting and design technologies to offer high power and high density through the compactness of their design, and Kubota's unique assembly methods produce a diverse array of engines that can be used in all kinds of different applications to meet a number of different needs.

Moreover, Kubota engines maintain high performance, while also being quick to meet the strict emissions regulations of various regions worldwide. It is a passion for creativity that has led us to these accomplishments. Our ability to simultaneously realize these differing objectives and achieve resonance with all kinds of applications is a major strength of Kubota Engine.

This meticulousness of design and passion for creativity is a common thread that links the works of Kubota Engine to those of Maurice Ravel.

Boléro has a simple structure, with a distinctive repeating rhythmic motif that crescendos from the start of the piece through to the end, and only two principal themes, but all the instrumental parts develop in a variety of different ways as they drive the piece toward its epic climax, making this a very appropriate piece to convey the 100-year story of Kubota Engine.

How Do Factory Sounds Become Music?

So, what sounds need to be made to produce a rendition of Boléro? When it came to the sound design for this piece, the production team undertook a process of trial and error, based on a number of approaches.

The music production work was undertaken by four Creators from the multi-award-winning music production company Syn: Music Producer Kazuyuki Haga, Composers Yuji Hagiwara and Mathieu Kranich, and Engineer Takashi Akaku.

First, they considered sound production based on four ideas:

- Using Boléro

- Starting with the sound of an old engine running

- Making music from recorded factory sounds

- Using actual engines as instruments

The team tried several different approaches to recording the sound of an old engine and having it transition into music.

But how do you take factory sounds and turn them into music? To explore that question, the team created at least 40 versions of the piece prior to actually getting recordings from the factories.

Here are some of the demos produced during that process.

Boléro: Rock Guitar Version

Orchestra sounds are added to the factory noises, and then a rock guitar brings the performance to life. It's a stirring work that appeals to the emotions.

Boléro: Samba Version

This arrangement has the rhythm of the engine performing the

role of samba-style percussion.

This version takes the unprecedented step of changing the time

signature of the original Boléro from 3/4 time to a 4/4 samba

feel. The music is actually performed by Brazilian musicians.

Boléro: Factory Sounds Version

This version of Boléro is made entirely from factory sounds. This demo is the closest to the final version, featuring simulated versions of actual factory sounds.

After much deliberation and consideration, it was decided that the simplest version of the piece, "Boléro: Factory Sounds Version" would form the basis of the new production, and so the team visited Kubota Engine factories to record the sounds that they heard there.

A Factory-ful of Sounds

Music Producer Kazuyuki Haga was apparently convinced that the team would be able to produce a good piece of music from the moment he arrived at the factory.

"This was my first experience of attempting to make music using only factory sounds, so there was no reason for me to feel as confident as I did. But when I actually visited the factory, I was reassured, because the factory was full of so many interesting sounds," says Haga.

The recording took five days. The team explored the factories while they were in operation and recorded sounds that caught the attention of their musicians' ears. Haga already had an idea in his head of how he wanted the music to be, so he searched for the sounds he wanted and put them together like pieces of a puzzle.

"I thought that there would be plenty of sounds that we could record as rhythmic elements, but to play the melody of Boléro, we needed some long, drawn out tones, so we took great care in searching the factory for sounds that could form the melody. We made recordings at all kinds of locations, all the while listening intently for the type of sounds that we wanted," says Haga.

The team became quite engrossed in their quest to record interesting sounds at the factories. Their next job would be to select sounds from the vast volume of audio data, and use them to create the music. This would be no small task.

The process of making music using recorded sounds instead of instruments is called sampling. Sampling is an approach commonly used in genres such as hip hop and dance music, in which an excerpt of a pre-existing piece of music or audio is reused in a different context to create a new composition. In some cases, tones from musical instruments and sounds from nature are recorded and incorporated into musical compositions.

For this project, however, the team did not add the sampled sounds to a musical performance, but rather created the music from sampled sounds alone. They therefore undertook the seemingly ill-advised task of listening to the entirety of the massive volume of sound data in order to create music using only those sounds.

It was composer Yuji Hagiwara who sorted the recorded sounds and arranged them into music. He described this sound production process in unique terms.

"This didn't feel so much like making music as it did making an instrument," recalls Hagiwara.

The task of selecting recorded factory sounds as if they were actual musical instruments, figuring out the pitch of those sounds, and using a computer to weave them together like a patchwork felt a lot like constructing a musical instrument.

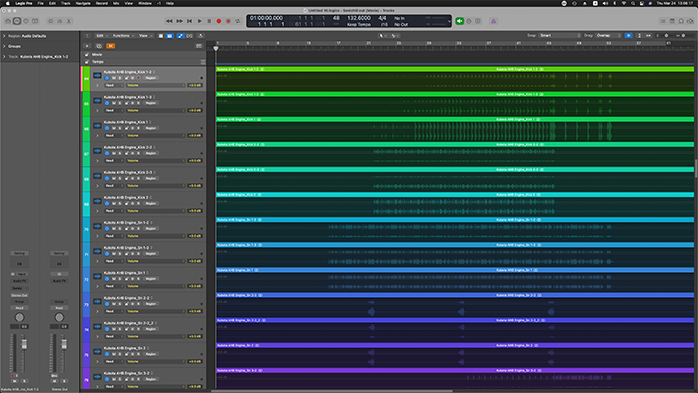

A screenshot of the extracted recordings being assigned to a musical scale, a process that felt like constructing a musical instrument.

"Of course, factory sounds don't sound at the exact pitch, so we started out by figuring out how to address that. We listened to the recorded sounds and figured out their pitch, with only our own ears to rely upon, sort of like 'this sound is a C. This sound is kind of like an E.' And that was the starting point," says Haga.

Anyone with absolute pitch can hear a sound in the natural world and figure out its pitch, so all of the sounds that we hear from day to day have a pitch.

For example, the grinding sound that is made when machining a cylinder head is an F, the sound made when tightening an oil pan nut is an A, and the sound made when applying a coat of paint is an E. After all of these notes have been selected, they can be assigned to the degrees of a scale, just like the keys of a piano. There are also long sounds, short sounds, loud sounds, quiet sounds and so on, so just one note, for example E, would need lots of different sounds from all over the factory applied to it.

That is why this process is similar to creating a musical instrument.

"First, we extracted and categorized the sounds that would be used for the melody and the rhythm. From there, we split the more delicate work among three of us and worked through the enormous amount of sound data to start putting sounds together. I believe it took our three-person team two weeks to do this," says Haga.

Reflecting on this undertaking, Haga declares with a smile,

"That being said, we had a really good time!"

Some of the actual recorded sounds:

The Ultimate Acoustic Sound

Once the sounds had been sorted and the "instrument" was complete, the team created the score, and over the course of two months, finished the music. Hagiwara took a central role in putting together the ensemble.

"The task of putting it all together as music also took a lot of time. For instance, we tried a few different techniques to make it sound more convincing as a piece of music, such as layering multiple sounds to make them sound like one note," says Haga.

"The sounds come across as quite simple in the final piece, but we layered sounds in complex ways to get to that point. The arrangement consists of over 100 different tracks," says Hagiwara.

The team used over 100 tracks to create a roughly 2-minute-long piece of music, in what turned out to be a complex process.

If we were to discuss the work of processing recorded sounds in terms that relate to Kubota Engine manufacturing processes, it could be considered comparable to machining: the raw materials need to be shaped and polished, and their strengths need to be brought out.

"That said, in processing the sounds, we have tried to make the most of the natural characteristics of each sound. We made almost no alterations to the sounds that we recorded, like adjusting the pitch. We wanted to use sounds that reverberate in the real world, in just the same way that bowing a violin string causes it to produce a sound, or blowing into a trumpet causes it to produce a sound. This is music made from raw sound. In other words, this could be called acoustic music," says Haga.

The music production team were careful to respect the characteristics of each sound, combining the attractive qualities of those sounds to create an acoustic orchestral sound the likes of which has never been heard before, not dissimilar to how engine parts are assembled to create a great diversity of engines.

"Although we played absolutely no instruments during this project, there was still a strong sense that we were creating music. It was very creative work," says Haga.

It bears repeating that this is not a conventional approach to music production. The team recorded the sounds of Kubota engineers manufacturing engines, and then used those sounds to create the rhythm, accompaniment, melody and harmony, without using any existing instruments. In this case, the team were not so much musicians as they were artisans who crafted a new and unique musical instrument.

"We're very excited for people to hear the sounds of factory machinery making music," says Hagiwara.

"This music incorporates all sorts of different sounds from the factories. So, every time you listen, you're sure to discover something new. I hope you'll listen to it again and again," says Haga.

When a Kubota engine creates sound, it also generates power.

And wherever there is power, society can move forward.

The accumulation of 100 years of wisdom built by Kubota Engine

has led to the factories of today.

And the sounds of these factories have transformed into music.

"This Sound. The beginning of everything."

That music is playing in the factories at this very moment.

And time continues to march on, toward the next 100 years.

Meet the People Behind the Music

Takashi Akaku

Recording and Mixing Engineer

After graduating from a vocational school, Takashi moved to

London to learn engineering at such locations as Abbey Road

Studios. He later returned to Japan, where he joined the team at

the recording studio Onkio Haus. In March 2001, Takashi joined

British music producer Nick Wood's Syn Studio as Chief

Engineer. Having worked in both Tokyo and

London, Takashi's work expresses a cross-cultural mindset. He

combines an analog sensibility gained through his work at a

long-established studio with the digital expertise that comes

from working with software like Pro

Tools.

Yuji Hagiwara

Composer

Yuji began working as a freelance composer and arranger at the

age of 21.

He has also composed for K-pop artists, Japanese pop artists,

and voice actors.

Yuji is responsible for the theme songs for a number of animated

series, and has produced a great many songs.

He currently works as an In-House Composer at Syn Music, where

he creates music for advertisements.

Kazuyuki Haga

Music Producer

Kazuyuki studied jazz drumming and composition at the Leeds

Conservatoire in the UK. After returning to Japan, he mainly

worked on music for theater.

He joined Syn Music in 2017.

Having worked as an Entertainment Coordinator, Kazuyuki now

works as a Music Producer and Writer.

Mathieu Kranich

Production Manager

Mathieu is a French composer and arranger who is based in Japan.

He studied musicology at universities in France and Italy,

before working for several years as a freelance musician in

France. Mathieu came to Japan in December 2019.

He began his career in music production at the music production

company Syn, where he works as a Production Manager.